Italy has a growing number of winemakers who have no pretensions to the international arena. They are passionate about using native grapes to make wines that set them apart from the herd. CARLO CAPALBO talks to some of them

The scenes in documentary film Mondovino which show Michel Rolland in the back of his chauffeur-driven Mercedes, laughing as he gives vinification instructions on his mobile phone provide an answer to the question of how a so-called ‘flying’ winemaker manages to keep on top of their vast portfolios of estates. Like so much in that film, the portrait comes close to caricature, but there’s no doubt that this sketch is light years from a winery owner’s dream of the soul-mate consultant who walks the vineyards with them and helps make personalised wines.

Italy has its own clutch of many a superstar winemaker, whose prize-winning ‘style’ can be felt – and often tasted – in their clients’ wines. Luckily, it also now has a number of highly talented, if less well-known, young people making distinctive wines for clients, or simply setting an example through their own winemaking.

What links their disparate wines, and personalities, is a deep commitment to wine as a direct expression of territory. They’re not concerned with building international profiles or tastes. Most only operate in small, specific areas of the great Italian patchwork of denominations and grape varieties. Their mission is to use native grapes and Italy’s varied landscape to make wines of personality, elegance (no over-oaking here) and terroir that set them apart from the crowd…

PAOLO CACIORGNA

Growing up on a farm is the perfect starting place for anyone wanting to work with the land and its produce, and Paolo Caciorgna considers himself lucky to have started life on one. In 1953, his father moved the family from Le Marche, where it was hard to find good acreage, to Tuscany, where new land-reform laws were redistributing feudal holdings. They settled at Casole d’Elsa, near Siena. ‘It was a good grounding: it taught me to accept the years and seasons as they come,’ he says, with characteristic calmness. His local school had just started an oenology course – ‘another stroke of luck’ – and that prepared Caciorgna for a degree from Siena’s Agrarian Institute and his first big job at Teruzzi and Puthod, the estate responsible for relaunching Vernaccia at San Gimignano. That was in 1985, when he was 21.

‘Enrico Teruzzi was obsessed with using technology to achieve quality results, and he was also a great businessman looking for a strong brand, both of which were useful lessons,’ Caciorgna says. After three years, he joined a lab specialising in wine analysis, where he attended daily tastings with the Tuscan old master, Giulio Gambelli. ‘That’s when I really began to learn how to taste wine. To experience red wines from Soldera, Cacchiano and Montevertine was a great schooling in Sangiovese.’

Young winemakers used the Isvea lab, and Caciorgna befriended and then joined Attilio Pagli and Alberto Antonini when they formed the consultancy group Matura. He worked with a range of estates, both in Tuscany and beyond, making reds and whites.

‘Almost all my whites undergo malolactic fermentation so they give more fullness in the mouth, more pleasure – as in Tamellini’s Soave, or Benito Ferrara’s Greco di Tufo. The south is a mine of varietals. Campania’s soil is very generous. Even simple native varieties like Greco or Pallagrello can produce great perfumes. In Puglia I’m working with Santa Lucia and its late-ripening red grape, Nero di Troia, and with Nerello Mascalese in Sicily,’ he says.

In late 2004 Caciorgna set up on his own. There were offers both from big industrial wineries looking for help in defining their wines’ styles, and from the smaller family-driven estates that Paolo has always felt an affinity for. ‘Planting a vineyard means putting down roots: where you plant, you live,’ he says, with his softly inflected Tuscan directness. ‘Italy’s patrimony is its vineyards, vines and soils. By saving them we also save the wisdom of the people who have always worked them.’

WINEMAKER CHRISTIAN PATAT

It seems fitting that a wine specialist from an area as culturally complex as Friuli should himself be comfortable wearing more than one hat. Christian Patat is part wine merchant, part oenological consultant. A jazz pianist who studied philosophy, he has a penchant for Burgundy and is a keen promoter of Friuli’s wines, the region he calls ‘a borderland.’ Patat, who is 37, has spent much of his working life selling wines, including a period as partner to winemaker Roberto Cipresso in Orchestra, an innovative consultancy and sales group.

‘My father was a gourmet and wine connoisseur who lived out his oeno-gastronomic passions hedonistically,’ says Patat. ‘He often took me on his road trips through France, visiting the estates whose wines he sold.’ We’re having lunch in Udine, Patat’s home town, and his own finely tuned palate is quickly apparent. If Patat’s role defies easy definition, there’s no doubt of the impact he has had in this area. In an informal way, he’s assembled a talented group of small Friuli estates that includes Le Due Terre, Miani and Davino Meroi – as well as one winery in Abruzzo and two in Piedmont – in which he occupies a key position.

‘Christian likes to operate discreetly, from the wings,’ says Serena Palazzolo, who Patat has been collaborating with for five years. ‘He’s of fundamental importance to each of us. A necessary figure but not a typical winemaker. In our case, he helps make decisions during the harvest, is present at tastings and blendings in the cellar, and advises us about sales or what wood to use. But what you value as much as his extraordinary knowledge about wine is his personal commitment.’ In other wineries, he’s an active voice.

‘Friuli is known for its whites but it can also make great reds. That’s unusual. Again, people associate Friuli with Pinot Grigio, but that’s the last thing most producers want to make,’ says Palazzolo. ‘I think of wine differently. I believe it’s an expression of terroir. I’m interested in the single site, the cru. And in the varieties that can best express it.’ In Friuli, these may be Tocai, Ribolla or Verduzzo; Refosco, Merlot or Schioppettino. Take Ronco del Gnemiz’ Tocai: it is very fine and long, it hasn’t undergone malolactic fermentation and has been fermented in barriques but doesn’t taste that way. ‘I like my whites dry and straight, with the nervous vein that comes from the ground’s minerality,’ he says.

https://www.decanter.com/wine-travel/italy/friuli-restaurants-hotels-and-shops-291893/

Patat is quick-thinking and articulate and has a vision for Friuli’s wines. ‘Modern Friuli was born 30 years ago when Mario Schiopetto brought in pure, clean, elegant wines like German Rhine wines. But today Friuli suffers from too many styles. I’d like to see a return to the dignity of the Schiopetto wines, to their rigour and classicism. I’m for refinement in wines rather than volume; the difference between a great and a good wine depends on the presence of the people who make it. It’s in the details that can’t be picked up by phone or email.’

WINEMAKER BARBARA TAMBURINI

It’s hard to believe that Barbara Tamburini has been able to cram so much into just 31 years. She exudes the quiet yet unshakeable confidence in her own abilities that often comes with someone much older.

‘I was very lucky,’ she says with a disarming smile. ‘On the day I graduated in viticulture and oenology from Pisa university, Nico Rossi from Gualdo del Re at Suvereto on Tuscany’s western coast, offered me a job. I was 26. “Either we adopt you or we hire you!” he said.’

Luck had little to do with it: she had been working there for a year as an apprentice and had already made her mark. ‘Nico understood my ideas right away. I wanted l’Rennero to become 100% Merlot.’

The true test of terroir is to compare wines from the same grapes grown in different zones, and this is illustrated when you taste l’Rennero side by side with the Merlot called Febo that Tamburini makes for Fattoria Sorbaiano, north-east of the coast, in vineyards at 350 metres. The freschezza and vivacity of Febo, with its mineral notes and attractive austerity, is quite different from the sunny complexity of the award-winning coastal wine. Yet both are well-balanced reflections of Merlot.

Tamburini also works successfully with Vermentino on the coast, Aleatico and Ansonica at Cecilia on Elba and Sangiovese, in its many Tuscan guises.

In five years she has taken on 22 other wineries – mostly in Tuscany – and makes weekly visits to nearly all of them. ‘I won’t stretch myself too thinly,’ she says. In 2001 she began working with some of those estates with the veteran winemaker Vittorio Fiore. ‘I think when we started, Vittorio imagined I’d be a glorified assistant, but we quickly found ourselves on a par. This is still a man’s world, but I’ve always believed in my professionalism. If men tried to dismiss me as just a pretty face, I never noticed!’, she laughs.

https://www.decanter.com/wine-travel/italy/top-10-tuscan-wineries-to-visit-13770/

Her proudest moment? ‘When I was allowed to fly with the Frecce Tricolori (the equivalent of the British Airforce Red Arrows) after being nominated Italy’s best young oenologist.’ She shows me a photo of a jet fighter swooping upside-down above the Italian coastline. ‘That’s me,’ she says, pointing to a tiny hand waving from the plane’s window. ‘It’s as close as I’ll ever come to being a flying winemaker!’

WINEMAKER PETER PLIGER

I like to think of Peter Pliger as the quiet man of Italian winemaking. He lives and works in a high rural valley – the Valle Isarco – north-east of Bolzano, in Alto Adige, the region that borders on Austria. He tends his vineyards himself, as he would a garden, maintaining an intimate relationship with every vine, stone and wild flower there. He doesn’t consider himself an oenologist, teacher or consultant, yet the model he sets by his way of living and working has encouraged many other winemakers in the valley to follow his example.

When I first tasted his wines, I was struck by their elegance and mineral quality, as much as by their purity and energy. His wines are all white, Sylvaner, Riesling, Veltliner and Gewurtztraminer, vinifed and bottled separately.

‘I like the challenge of extreme experiences,’ says Pliger, as he shows me a vineyard he has bought, at 700 metres. ‘It’s in one of the valley’s best positions, but I got it cheaply as no road reaches it and the dry-stone wall terraces will have to be rebuilt.’

Wines were made in this area for at least 1,000 years, but over the last 50 many vineyards were abandoned. The current revival is thanks mainly to Pliger’s decision in the 1980s to start making wine from his father’s disused vineyards. ‘I studied commerce, but hated being trapped in an office, so I became a carpenter,’ he says.

His wife Brigitte came from a farm nearby, and encouraged him to work the land. ‘It was all trial and error at first but I discovered I had an affinity for the vine,’ he says. The first few bottles were sold to a local chef who wanted more, and who brought in winemaker Ignaz Niedrist to give him some early guidance. That was in 1990, and Pliger never looked back. Over time, he gave up using chemicals and fertilisers. ‘My Kaiton Riesling is quiet to the nose at first, but you sense its depth, and you taste how extreme the territory is, how hard a life the plants have,’ he says. ‘These are vini veri – real wines.’ His wines are fermented at temperatures of 20-22°C (not too cold or they become aggressive), never undergo malolactic fermentation (or they lose their crispness and longevity), and rely on native yeasts.

Seeing Pliger’s success, other local growers began vinifying their grapes. ‘Pliger – or ‘the philosopher’ as we call him – doesn’t talk much, but he’s been an instigator,’ says Manni Nössing, one of the area’s most talented young producers. ‘He saw the potential in the valley and in our native wines, and brought us all together to make them.’

WINEMAKER BEPPE CAVIOLA

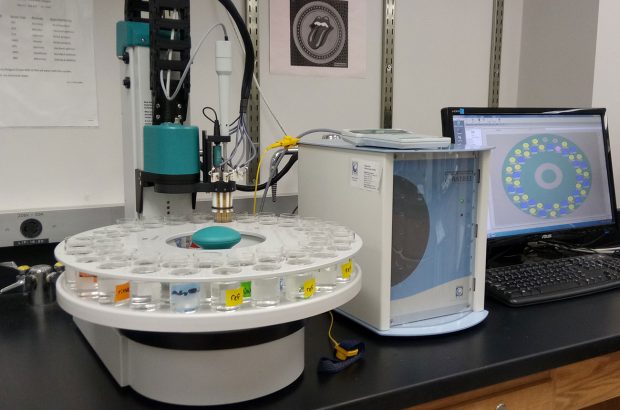

It’s a grey autumn day as I drive through the misty Langhe in Piedmont to meet Beppe Caviola at his winery in Dogliani. The harvest is beginning here, as in other parts of Italy, and the phones at Ca’Viola are ringing constantly. Caviola has client estates throughout Italy and also runs an analysis lab, Vino Veritas, with his wife Simonetta. Beyond the small but efficient cantina is what reminds me of a French hôtel particulier, which is being turned into the Caviolas’ house, and an agriturismo. The vineyards are nearby, at Montelupo Albese, 12 kilometres from Alba.

‘Montelupo is known for Dolcetto,’ says Caviola, as we sit at the sleek, white tasting table. ‘My father and grandfather were butchers and owned a little land there for growing vegetables and grapes.’ As a child, Caviola, who is 43, often accompanied his grandfather into the vineyard. Later he studied oenology at Alba, before taking a job at Carlo Drocco’s Oenology Centre, a wine analysis laboratory. There he met many of the pioneer winemakers of the late 1980s, including Domenico Clerico and Elio Altare.

‘Altare opened my horizons about wine. He took me to Burgundy and encouraged me to start experimenting. It hadn’t even occurred to me to bottle it.’ Caviola teamed up with another lab attendant, Maurizio Anselmo, to form Ca’Viola – the ‘purple house’, a play on his surname. Their first vintage was 864 bottles of Dolcetto from a zone called Barturot. ‘Dolcetto was considered an easy, second-string wine by everyone but producers like Quinto Chionetti,’ he explains. ‘That’s hardly surprising, given that most of it was being bottled by Christmas,’ he adds.

Caviola took it more seriously, applying the logic and care the great Barolisti gave their Barolos. ‘From the start we wanted to make grande Dolcettos,’ he says. Today’s Barturot is plum-purple and rich – a very pleasurable wine with natural, silky tannins. He has stopped using oak on it. ‘What’s the point of covering the fruit?,’ he asks.

Caviola now owns seven hectares. With his help, other Dolcetto producers in the area have changed tack, and style, with great results. ‘The Langhe is in the hands of small vignerons and we can’t afford to let the side down. Every grape variety deserves equal respect.’

MARC DE GRAZIA: Marc de Grazia isn’t an oenologist as such, yet his deep knowledge about wine and his infallible ability to find promising talent and terroirs has, for over 20 years, made him one of the most interesting promoters of Italy’s crus, there and abroad. Look for: Salvatore Molettieri Taurasi Riserva Cinque Querce 2001 *****

SALVO FOTI: Linked irrevocably to the terroirs of eastern Sicily, Salvo Foti is a young traditionalist making distinctive, modern wines from native grapes in volcanic soils with Sahara-hot climates. Look for: Benanti Etna Bianco Superiore Pietramarina 2001 *****

CELESTINO GASPARI: Celestino Gaspari is an oenologist working exclusively in Veneto. He has put himself behind a lot of the up-and-coming young estates in and around Valpolicella. Look for: Tenuta San Antonio Amarone Campo dei Gigli *****

LUIGI MOIO: Son of a Campanian pioneer winemaker, university professor and oenologist Luigi Moio trained in France. He has become a specialist of Aglianico and other native grapes from different areas within this important southern region. Look for: Luigi Maffini Pietraincatenata 2003 ****

FABRIZIO MOLTARD: A native of Piedmont, agronomist Fabrizio Moltard moved to Tuscany to work with Gaja before going freelance and is now the secret ingredient in many top Maremma wineries. Look for Montepeloso Nardo 2003 *****

CARMINE VALENTINO: Campanian Carmine Valentino works as a consultant winemaker for a handful of some of Irpinia’s most touted young talents, whose wines’ common denominator is elegance, minerality and length. Look for: Pietracupa Fiano Il Cupo 2004 ****