If you have any spare time coming up over the holidays, I could send you a copy of Philippe Starck’s CV.

You’ll need fortification at hand, because it might take you a while to get through the 22 closely-typed pages. They detail, among other things:

- the 100+ hotels, bars and restaurants that he has been responsible for as both an interior and exterior designer;

- design work on 22 vehicles, including sailing boats, electric cars and mega yachts, plus a stint as art director for the Virgin Galactic spaceport;

- many, many hundreds of tables, chairs, lights, accessories, kitchen utensils and luggage designs that he has brought to market.

The list of awards he has received takes up five pages alone.

This is a man who, somewhere over the course of the past five decades, has slipped into our everyday consciousness in a way that is normally reserved for musicians and film stars.

I have six of his ‘Victoria Ghost’ chairs around my dining table downstairs, and a ‘Miss K’ light next to the sofa. I can remember my mother buying a Starck bathtub in the 1990s and neighbours actually coming round to admire it.

All this because he manages to combine extreme ubiquity – most of his designs are made on an industrial scale, making them financially approachable and widely available – while remaining boundary-pushing and continually surprising.

So I guess we should have expected that Starck would not be content to accept the status quo when heading into the world of wine.

His CV reveals a few forays into food and drink, detailing design work for an organic olive oil in 2004, a beer bottle for Kronenbourg in 2002 and two mineral water bottles, one with Vittel in 1984 and another with St Georges in 1995.

In his own words: Philippe Starck on Roederer

But, for the more recent projects, he was not content to simply design the outside of a bottle. This was most notable when he launched his own Champagne with Maison Louis Roederer; the Brut Nature 2006 was the first new cuvée from Roederer for more than 40 years.

‘We have Champagne in my family DNA,’ Starck said.

‘One of my earliest memories is of our back garden littered with Champagne corks after a party. It’s a childhood image that has stayed with me all my life. But I didn’t want to inspire people to drink something unless I was responsible for what was inside the bottle as well as outside.

‘When Frédéric Rouzaud [owner] and Jean-Bapiste Lécaillon [chef de cave and executive vice president] asked me to work with them at Roederer, I refused unless I was able to create the Champagne as well. They were surprised, but they agreed and took a chance to trust me.’

He added, ‘I of course didn’t know how to make Champagne next to a genius like Lécaillon, but I knew what I wanted and gave him clear images that corresponded to the taste I was looking for – words like vitality, life, modernity, infinity, minimal, metal – that he was able to translate into chemistry.

‘He matched the terroir and style to my words, finding the exact limestone-heavy spots in their vineyards to create the flavour and aroma profile that I was looking for. We worked together, and created a new category of Champagne for the Brut Nature; zero dosage, bone dry, no added sulphites. It was not certain that it would work, but the whole team was delighted.’

Roederer recently launched Brut Nature Blanc 2012 in collaboration with Philippe Starck, as well as a rosé Champagne from the same vintage.

Going ‘minimalist’ in Bordeaux

Starck’s design for Carmes Haut-Brion, completed in 2016.

Similarly, for Château Carmes Haut-Brion’s new cellar in Pessac-Léognan, completed in 2016, the intention was to create something that had not been seen before among a rash of new building projects by prestigious architects from Jean Nouvel to Sir Norman Foster.

‘I took a minimalist approach,’ said Starck. ‘[It was] very different from many other Bordeaux châteaux, using cement for the building material, with a metal skin wrapped around the outside, clean and simple [with] all the technology hidden [and] temperature regulation coming from the water of the lake that the building sits within. It’s low high-tech. Sophisticated but extremely well hidden.

‘I am the son of an engineer, and I am very interested in chemistry and geothermal technology. This cellar was conceived to make the process [of] winemaking as efficient as possible.’

Getting a taste for wine…and vinegar

Starck was born in Paris in 1949, making him an extremely young 70-years-old this year. His appetite for wine, and specifically for approaching it a little differently than most, dates back to his childhood.

‘My mother had an extraordinary cellar. Every birthday we would drink from the birth year of whoever was celebrating, [and it was] always wonderful bottles of Bordeaux and Burgundy. She allowed us to drink wine from an early age to ensure that there was no mystery to it when we went out with friends later on.

‘My father’s influence was more eccentric. He drank good wine, but also balsamic vinegar and garum / nuoc-mâm [a fermented fish sauce]. He used to drink vinegar with his friends for an aperitif. I also have made my own vinegar, from brut nature organic Champagnes, and enjoy it very much.’

New project: Biodynamic wine that ‘no one else will like’

Today he is flexing his muscles even further, by planning to make his own wine at his 35ha estate in Grandola, an area that sits to the north of the Alentejo region of Portugal overlooking the Atlantic ocean.

The intention is to plant a few rows of vines that stretch between two buildings on the property, with the vines lining either side of a walking path.

‘We will begin moving the earth for planting next week, and I hope to be bottling my first harvest three years from now.

‘I want to make a wine just for me, and am sure no one else will like it. I plan to make just 400 bottles in my tiny cellar that looks like it was created by Hermès.

‘I am intending to make an organic, biodynamic, unfiltered, no added sulphite red wine… and to make it sparkling. You see, it is unlikely to please many people. But luckily I have friends who make great wines, so I can happily make a terrible one that is just for my own enjoyment.’

He enthused about his love for ‘explorer’ wines from small producers, made by ‘extreme radicals like myself’.

Classic vs radical

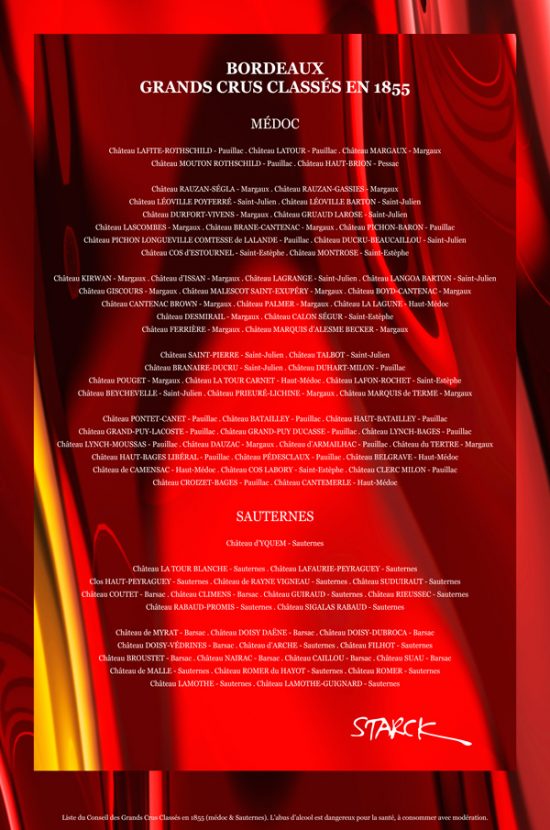

This focus on unexpected flavours and techniques made me query his latest project in Bordeaux, unveiled this week, which is a poster for the 1855 Grands Crus Classés châteaux.

It will form the third in a series of posters made for the group, following the inaugural one by English painter Carl Laubin in 1989, and a second by photographer and environmentalist Yann Arthus-Bertrand in 2008.

‘The Grand Cru Classés of Bordeaux were once radicals and have become classics, but retain their sense of mystery,’ he said.

‘I love great Bordeaux because it is a product of human intelligence. They were not created overnight, they are the result of practical intelligence, each bottle and vintage bringing new understanding over generations.

‘Wine itself is the work of thousands of people over thousands of years, saying ‘how can I do better?

‘These wines are the result of that ceaseless search for improvement. When I see them, I see all the mental processes that they represent, the work that goes into understanding the vineyards and the process of creating them through chemistry and art.’

How the poster was created

‘For this project, I was not interested in bottles or labels, just the wine itself. I wanted to penetrate into the heart of the liquid. For months we worked with a computer to recreate the movement of this incredible liquid; the shadows, the light [and] the texture, to see the sensual fluid nature of wine.

‘I wanted to create a microscopic eye that would enter into the heart of the liquid, and used a lenticular technique that gives 3D images of movement.’

I guess in the end classified Bordeaux is as much a symbol of French excellence and savoir-faire as is Starck himself. Both have shown an ability to stay relevant across different generations, and to reinvent themselves in surprising ways.

‘I don’t hold on to memories,’ Starck said. ‘I don’t know if I am lucky for this to be the case or not, but that is the way I am.

‘It means that the moment a project is finished I forget it. It permits me to look at my finished work with new eyes, to see how to do better next time. And to move on to the next thing.’

Read expert reviews of Louis Roederer and Philippe Starck’s Brut Nature Champagnes:

More from Jane Anson:

Exploring Closerie-Saint-Roc, a new cult wine in Bordeaux?

Great novels for wine lovers