- The Spanish perception of sherry could hardly be more different from ours.

- In recent years, improved handling and temperature controlled vinification have removed much of the uncertainty which used to result from foot treading and barrel fermentation.

- There are significant variations within the sherry region, right down to a microclimatic scale where differences occur between adjacent bodegas.

- Improvements in single-solera fermentation mean that the final alcoholic strength of manzanilla and fino has fallen in recent years.

Few places in the world eat, live, drink and breathe their wine in the same way as Jerez. Other towns and cities synonymous with great wine – Bordeaux, Beaune and Oporto spring to mind – are somehow demure by comparison.

The Jerezanos seem to turn the day on its head. They start work at around 7am and continue until 3pm. By this time, in the summer, the searing heat is little short of unbearable. From mid-afternoon the streets are deserted as people take refuge from the sun in cool, dark bars, followed by lunch and a much-needed siesta. Then, just as the burghers of Beaune and Bordeaux are setting up the shutters for the night, Jerez comes to life. Someone strums a few chords on a guitar and by 10pm whole towns are pulsating to the rhythm of the local dance, the Sevillana. Dinner is rarely served before 11pm and by the time other self-respecting people in the wine world are making cups of cocoa and turning in, the Jerezanos are in full swing: stomping, clapping and drinking.

You only need to spend a day in Jerez to find out what eggs them on. Half-bottles of fino or manzanilla stand in ice buckets on the bar to be served on their own in cafés, with appetising tapas before lunch and dinner or right the way through a meal of fresh, locally caught fish. Sherry is, therefore, an integral part of the day-to-day way of life.

The Spanish perception of sherry could hardly be more different from ours. Whereas medium and sweet styles of sherry account for over 80% of the British market, pale dry fino and manzanilla are a fashion statement currently representing 85% of Spanish demand. They treat it like a white wine – which, of course, it is – serving it cool in a tulip-shaped copita. With an annual turnover of around 14 million litres, bottles of fino and manzanilla don’t hang around for long and there is little chance of being presented with a glass of tired, oxidised wine.

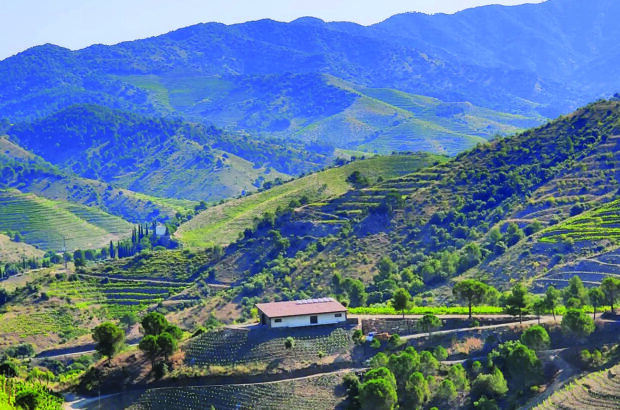

But fino and manzanilla are white wines with a difference and, just as that other great, uplifting aperitif, Champagne, is very much a product of the climate and landscape of northeast France, so sherry reflects the unique physical conditions of this corner of Andalucia. First there’s the soil: the brilliant white albariza where the Palomino grapes destined to produce the finest and most delicate finos and manzanillas are grown. Then there’s the climate, in particular the cool breezes that blow off the Gulf of Cádiz encouraging the growth of the flor yeast which shapes the character of the wine as well as accounting for the differences in style between fino and manzanilla.

In the past, sherry producers have gained some of their approbation by wrapping their art in a cloak of mystique. But, in recent years, improved handling and temperature controlled vinification have removed much of the uncertainty (and some of the mystique) which used to result from foot treading and barrel fermentation. Although the process is still complex, grape must destined to become fino or manzanilla comes from the first and most gentle pressings and tends to be fermented at lower temperatures than that destined to become a medium-dry sherry or oloroso. These fresh but neutral base wines are then fortified to around 15%. The growth of flor on the surface of the wine is inhibited by alcoholic strength any higher. The huge sherry bodegas are teaming with these yeasts which are extremely sensitive to the ambient temperature. For example, inland in Montilla (an area known as the ‘frying pan’ of Spain), flor is reduced to a scum-like film in July and August, while in the marginally cooler, Atlantic-influenced climate of Jerez it continues to flourish all year round.

But there are significant variations within the sherry region, right down to a microclimatic scale where differences occur between adjacent bodegas. Flor tends to maintain a thicker and more even film in those bodegas located in the cooler maritime towns of Sanlúcar de Barrameda and El Puerto Santa María than it does in the city of Jerez itself. The consequence of this is that three distinct styles of pale dry sherry are produced: fino, Puerto fino and manzanilla (see box).

Left entirely to its own devices flor would quickly run out of nutrients and die back causing the wine to oxidise before the yeast had made a profound impact on the style and character of the wine. Flor is therefore sustained by continual refreshing and replenishing with younger wines. This is the basis for the solera system, a method of fractional blending which apart from nurturing flor in finos and manzanillas also helps to maintain a consistent house style.

The solera system is often misleadingly depicted as a pyramid of casks with the top level (or criadera) feeding the next and so on until the wine is finally withdrawn from the bottom tier, the solera itself. In reality soleras are much more complex with as many as 16 separate criaderas, sometimes spread among separate bodegas in different parts of the town. One of the most exciting and instructive tastings anywhere in the wine world is to follow the cellar foreman around the bodega and taste the wine from different criaderas, following its development until it reaches the final solera. The rather

simple, fresh appley young wine (the añada) gradually gains character from the flor. At first this manifests itself with overtones of Chinese spices, taking on typically incisive savoury, dough-like aromas and flavours with age. Depending on the extent and complexity of the solera system, this represents a vertical tasting spanning up to 12 years.

Whereas a fine old oloroso may be cross-blended from a number of soleras, the finest manzanillas and finos are usually drawn from a single solera and bottled without further ado, apart from the necessary clarification, refrigeration and filtration. Improvements in the latter mean that the final alcoholic strength of manzanilla and fino has fallen in recent years. Most finos used to be fortified for a second time taking them up to 17.5%, but the legislation has recently been altered to allow wines to be shipped at the bodega strength of 15%.

Although many of the lighter finos have an immediacy and vibrancy about them, I still retain a preference for wines at the slightly higher strength. Not only do they seem to have more character and pungency, they also keep rather better in bottle both before and after opening. This is a distinct advantage back in distinctly ‘cool’ Britannia where few sherry drinkers stomp and clap their way through the night accompanied by copita upon copita of fresh, chilled fino.