- In the 1980s producers realised that something needed to be done for Navarra to be able to compete in the world’s quality markets.

- The local government set up a research station with a brief to examine every aspect of viti- and viniculture: soils, rootstocks, clones, fermentation, ageing.

- Bodegas were encouraged to get rid of their concrete vats and re-equip with stainless steel, and œnological research was made available to winemakers.

- Navarra has leapt from almost dinosaur status in 1980 to its present position as one of Spain’s most innovative and exciting Denominaciones.

‘After phylloxera, it was an unfortunate decision to plant Garnacha,’ says Sonia Olano of Bodegas Castillo de Monjardín, and she echoes the feelings of many of her colleagues in Navarra. Garnacha is a workhorse grape, and in monoculture it turns out large quantities of good quality, modestly-priced, immediate red and rosado. There are a very few ancient vineyards (mainly in Priorato) where it achieves spectacular results, but only at the kind of yields which would bankrupt the average commercial-scale winery. Garnacha’s great strength is its ability to add warmth and ripeness to a blend of more austere varieties (typically Tempranillo and latterly Cabernet Sauvignon), but that isn’t something you can build an export market on in 1998, especially when it covers 90% of your vineyard.

The problem has been a long time coming: in the 1920s Navarra’s vineyards covered some 50,000 hectares (ha), but by 1980 this had fallen to around 13,000ha (the 1997 figure is 13,171ha). This was simply because farmers gave up on viticulture as a way of earning a living and switched to other crops. By the end of the 1970s Navarra’s reputation was firmly pigeonholed; sub-Rioja reds at lower prices and nice-but-lightweight pinks for the holiday trade. A hundred years after phylloxera, had all the work been in vain?

In the first place, why did they replant with Garnacha after the bug in 1892? The reason is probably twofold. Firstly, 40 years before phylloxera, Navarra shared the western-European vine-plague of oïdium and replanted laboriously, only to see all that work wiped out a generation later. Secondly, Garnacha is a tough, disease-resistant grape which matures early and produces good, if only rarely great, wine. It had the ring of reliability and the only other option was to replant with Tempranillo, which was horrendously expensive and could, in any case, have brought Navarra into nose-to-nose confrontation with its rich and mighty neighbour, Rioja. So, Garnacha it was.

Nearly a century later, in the early 1980s, the world had moved on, quality was the market’s watchword, and Navarra was losing out. Most of the wine (85%) was being made by co-ops and nearly all exports (70% at that time) came from one company, Bodegas Julián Chivite. Something needed to be done for Navarra to be able to compete in the world’s quality markets, but no company had the resources to do it single-handedly. For this reason, the local government set up a research station with a brief to examine every aspect of viti- and viniculture: soils, rootstocks, clones, fermentation, ageing…. This is what became EVENA, the Estación de Viticultura y Enología de Navarra, and its work over the past 15 years has underpinned all the revolutionary changes which have taken place in the region.

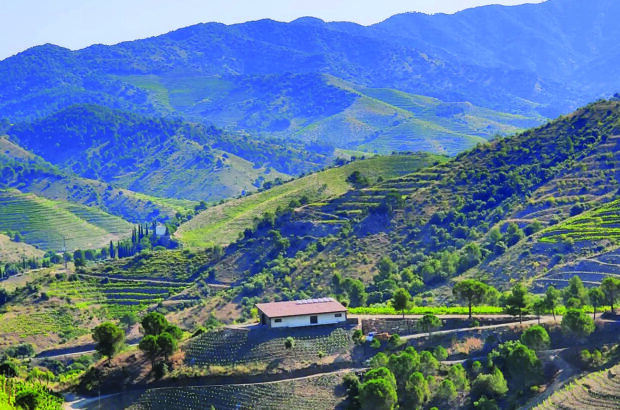

The first and most fundamental changes came in the vineyard. New varieties of grape were evaluated by EVENA and passed for winemaking, and the Consejo Regulador actively encouraged growers to replant with Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon and Graciano. Although the main thrust of Navarra’s ambitions for the next century are centred on its native grapes – particularly Tempranillo, Garnacha and Graciano – the planting of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and other ‘foreign’ varieties (more than 40 have been or are being evaluated) was an inspired move. These grapes are effectively (if not quite totally) proscribed in neighbouring Rioja, and the vineyards of Zaragoza, Navarra’s southern and eastern neighbour, are too arid for them. In this way, the region is able to produce something uniquely ‘Navarro’, different from the wine of its immediate neighbours, as well as providing extra opportunities for experiment. Tempranillo-Cabernet and Tempranillo-Merlot wines are finding favour with a number of bodegas and, of course, experimental varietals of everything from Pinot Noir to Syrah can be found by the enthusiast.

Meanwhile, EVENA continued with the unsung background work. This included assessing rootstocks; out went the ubiquitous Rupestris de Lot and in came a variety of roots each selected for its affinity with a particular soil-type: like 99 Richter (good for drought conditions in the south), 420a Millardet de Grasset (great in chalky soils) and SO4 (good in fertile soils). Bodegas were encouraged to get rid of their concrete vats and re-equip with stainless steel, and œnological research was made available to winemakers. Finally, in the cask-cellars of the region, EVENA conducted exhaustive tests on oak types, varying degrees of toast and the effects of older and newer casks on the wines. The results, whilst not an exact science, have enabled Navarra to leap from almost dinosaur status in 1980 to its present position as one of Spain’s most innovative and exciting Denominaciones.

Let’s look at the differences: in 1980, Navarra was 90% Garnacha and turned out mainly rosado wines with little or no market beyond the region. The few reds were mainly sub-Rioja blends of Tempranillo, Garnacha and Mazuela with a bit of new oak – not bad wines, by any means – but not cheap enough to convince people that they should be buying Navarra instead of Rioja. In 1998, however, Navarra is bursting with export energy, still led by Chivite in Cintruénigo, but now joined by such long-established names as Ochoa in Olite, Magaña in Barillas, Guelbenzu in Cascante and the Señorío de Sarría. Each of these re-equipped and replanted in the 1980s, perhaps most notably Ochoa, whose president Javier Ochoa was for many years the driving force behind EVENA, and Guelbenzu, whose vineyard was completely replanted with Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Tempranillo after over 100 years of obscurity. If these are the leaders of the new wave, then others have not been slow to follow: Bodegas Principe de Viana at Murchante and Vinícola de Navarra in Campanas, for example, have developed major exports in the mid-market sector.

The real test of a region’s success, however, is whether its growth and resurgence is bold and promising enough to attract investment from outside. New names added to the Consejo Regulador in the past 10 years include Marco Real (1988) in Olite, Castillo de Monjardín (1988), Palacio de la Vega (1991) in Dicastillo, Orvalaiz (1993) in Obanos and Nekeas (1994) in Añorbe. New styles of wine include Cabernet, Merlot and Tempranillo blends and monovarietals, some with a little oak age rather than full crianza, and let’s not forget Navarra’s whites: pleasant if a little squeaky-clean, Viura has given way to Viura-Chardonnay blends as well as barrel-fermented Chardonnays and even Ochoa’s award-winning sweet Dulce de Moscatel. And, of course, good old traditional Tempranillos and Garnachas are still with us, as well as the (still very acceptable) rosado.

So, having come this far, where is Navarra heading? I asked a number of winemakers for their thoughts. Juan Narvaiza of Señorío de Sarría says that the future lies in two directions, maintaining the quality of traditional and new-wave wines. He believes that Navarra is strongest in reds, well extracted, with the accent on fruit and just the right amount of crianza (regardless of regulations) to suit each wine. He says Navarra should use its natural advantages in soil and climate to maximise the grapes’ potential, and he’d like the name ‘Navarra’ on a bottle to be, as well as a guarantee of origin, a guarantee of quality.

Olano of Castillo de Monjardín, one of the first bodegas to plant the newly-permitted varieties, hopes that the lessons of the past will help Navarra to take advantage of its new ability to experiment and exploit classic varieties to produce lower yields and better grapes, such that Navarra becomes associated with modern, well-made, high-quality wines.

Miguel Merino of Bodegas Ochoa expresses his delight that the markets so readily accepted Navarra’s new-wave wines, and also that not just the wines from the ‘great and good’ have improved. Everyday Navarra wine is better than ever, he says, which, of course, strengthens the generic name, and customers are more likely to ‘trade up’ to a good Navarra for a special occasion.

So, 12 months away from the next century, is everything in the Navarra garden lovely? Well, perhaps not quite. Olano strikes a note of caution: some of the newer wineries, she warns, are after a quick profit and are releasing their wines too soon. Wine is a long-term business, she says, and we must all be patient. This is a particular problem after three years of drought and short vintages in the early 1990s, but patience is a virtue. Let us hope that the bodegas of Navarra, after 20 years of toiling in the vineyard, don’t throw away their manifold advantages on the altar of accountancy.